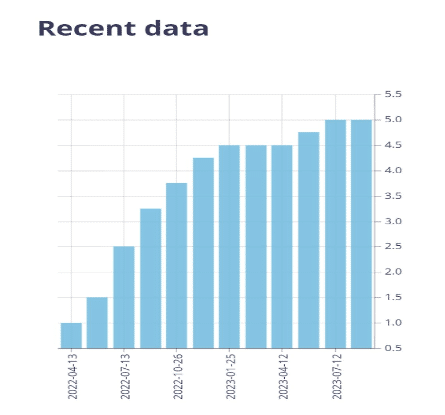

Higher interest rates are starting to bite.

Mortgage renewals are making some homeowners’ stomachs churn and business borrowing is getting quite expensive, prompting some political leaders to take aim at the central bank.

At both the federal and provincial levels, politicians attacked the Bank of Canada for raising rates to five per cent over the past 18 months.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford said the rate increases were causing homeowners and small businesses to wobble, and added that he thought the Bank itself is responsible for high rates of inflation seen in Canada since early 2022.

And B.C. Premier David Eby wrote a letter, saying rate increases are hurting “the middle class and everyone below that,” in the form of higher mortgage payments and rents.

Federal conservative leader Pierre Poilievre went a step further, saying he’d fire Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem if he was prime minister.

For his part, Macklem told reporters the central bank remains “independent” despite the flurry of criticism it has received from political leaders.

In his speech earlier in Sept. 2023, Macklem said repeated increases to the key overnight rate are slowly bringing inflation down, but not quite fast enough for his liking.

“Consumer price index (CPI) inflation was 3.3 per cent in July, roughly in line with what we expected in our July Monetary Policy Report,” Macklem told an audience in Calgary. “Our two per cent target is now in sight. But we are not there yet and we are concerned progress has slowed.”